Jump in Bump

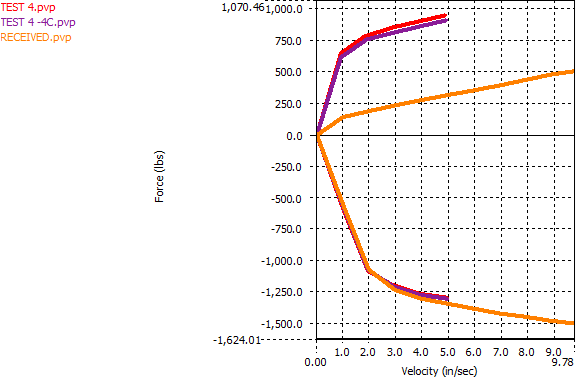

Got a fresh shock dyno today, this is about the most bump Penske could get with its existing internals without risking shock cavitation, even with gas pressure pushed to the limit.

Apparently they have a lot of experience with very-high-rebound setups, as it’s what all the Nascar guys use to control their chassis that run around on bump stops most of the time. But nobody seems to be going after those crazy low-speed bump forces.

(orange is baselie valving, red is new at full stiff, purple at 3 clicks off full, as far as can go without cavitating)

One must remember the Camaro shock is mounted about 9″ out on the 16″ long arm. You have to multiply x .316, and be looking at 2in/sec here, and compare that to the raw values at 3in/sec, you’d see on a strut car like a BMW. 240lbs. @3in/sec is maybe a bit high, but not out of bounds. Ditto 350lbs @3in/sec for rebound. But that is the horribleness of the Camaro suspension – it takes high-end modern shocks pushed to their limits, to achieve damping effectiveness on par with “normal” performance dampers on a better-suspended car. I can go a bit further with both bump and rebound with these shocks, but doing so would require changing out a lot of their guts, and I wanted to be sure to get them back and installed in advance of my next event May 19.

It’s possible this will be “too much”, and the car will want to push. I am ok with push in transitions (prefer it really), but if the car bulldozes in steady-state, I can reverse some of the other changes made (by softening the front swaybar and raising the rear roll center) to correct things in the other direction.

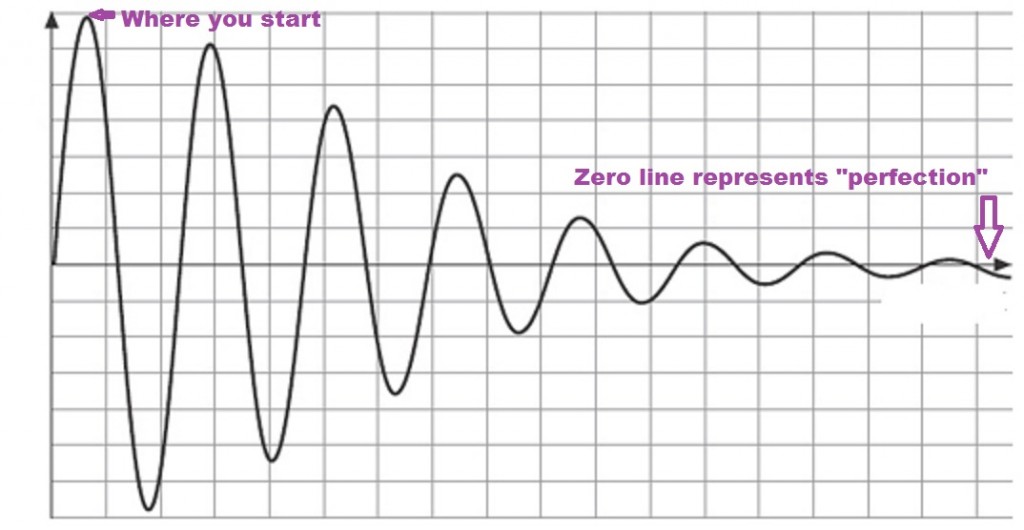

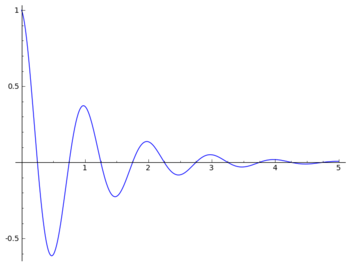

The subject of dampers has some parallels to my overall theory of car tuning. I think of tuning like a decaying, or damped, sine wave. In it, you start off at an amplitude or Y value very far from zero, which itself represents perfection. Over time, you make changes that you hope get you closer, knowing you’ll never land exactly on it – there are too many variables. But you keep making changes, and with experience and knowledge gained, begin to make smaller and smaller adjustments as you hone in on “perfection”, which is never actually achievable.

Tricky things come along like a new tire to test, or new preparation allowances, even a new surface, that move the perfection line around, and perhaps necessitate some big changes to get back to within the same distance of perfect.

It illustrates a little bit, how you have to know what changes and adjustments to make, and be able to evaluate whether you are getting closer to, or farther from, perfection. You also need to know if the change was too big and you overshot things, or if it wasn’t enough, and there is still more to do.

Really good tuners of cars can get closer to perfection more quickly – just like firm dampers don’t let your springs oscillate too much…

I certainly don’t think I’ll be anywhere close after only 4-5 tuning iterations or cycles given how radically far off the car was to start with, but it should continue to get better and better. The difficulty in wrangling this beast both from the tuning and driving angles, is part of what makes it so engaging.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.