Rear Shocks

This week both front and rear shocks arrived for the Camaro.

Despite my history of nothing but satisfaction and success with the 28-series Koni shocks, for this car, I have chosen to give the Penske platform a try, for a few reasons-

- They offer some more modern valving options not available in the typical 2812Mk2 bodies I’ve run. Will explain that below.

- I do have some experience on Penske triple adjustable shocks – the Lexus IS300 owned by Jason Uyeda I drove a bit in 2005 had them, and they worked great. Also, Doug Hayashi’s Honda S2000 we ran in the 2003 Open Track Challenge had a set built and valved by Erik Messley, and that car was sweet too.

- The people I use to build my shocks, ProPartsUSA, has experience with Penske, and would be able to help me out. I wouldn’t have tried this were it not the case.

- I need *some* excuse to run some kind of Penske sticker on the car. The classic Trans-Am cars always had “Penske-Hilton Racing” or “Penske-Godsall Racing” on the front fenders – if I put “Penske Racing Shocks” in the same spot, should give it the look without being totally illegitimate. Of course advertising for people when you don’t have to (not like anybody is cutting me deals) is kinda silly IMO so who knows what will go there.

What actually got me started down this path was ProParts mentioning they had a set of very high-end 8765‘s sitting on a shelf that they’d used for a test but never on a car, that they could pass on for a very good price. Their dimensions put them in range for the rears, so they proceeded to build them.

Not having built/tuned a live axle car before, many aspects of what comprises an “ideal” rear shock valving are at this time a mystery to me. Some things are known – spring rate, ride frequency, and motion ratio – which, unlike so many aspects of this chassis, actually isn’t a problem. It is basically 1:1 in bump, and close to it in roll. I also know my own preferences – which in general, are to run the rear shocks fairly soft. Too much rear compression, and you risk “blowing the tires away” with a rapid throttle press. Too much rear rebound ups the chances of losing the rear end in a transition type maneuver.

Of course, too little, the car feels dead, and difficult to make “dance” through tight spaces, of which we have plenty in autocross. In my experience if you have a fairly well balanced RWD chassis (either naturally like a Viper or with freedom over bars and springs like an STS 240sx), softer rear shocks are something that makes a car easier to drive, helping you minimize the frequency and magnitude of mistakes, even if maybe it sacrifices ultimate potential a little.

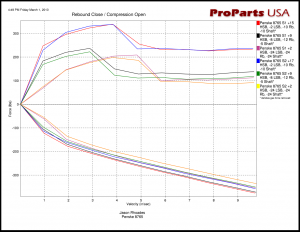

All that said, here’s a few dynos of the rear shocks-

On the rebound side, we have modest forces, and a mildly regressive curve. This shock will be operating around 3in/sec for typical (non-bump) autocross maneuvers. I would have like a slightly wider range of adjustment with another 20% available both below and above this range, but all told it’s probably about where it needs to be anyway.

Things start to get really interesting on the bump side, and this is where the 8765 separates itself from the more-common 8760. Note in the legend at the upper right, there are four dimensions given for each dyno:

- HSB

- LSB

- Rb

- Shaft

Aaaack! Four adjustments?!?!?! In the picture above notice there are two wheels in the eyelet at the end of the shaft, and there are two knobs at the end of the canister. At the other end of the canister is the Schrader valve for gas pressure, which one could even consider a fifth adjustment – oiy.

For those that haven’t seen it, here is what I consider an excellent, clear and concise guide to shock tuning by Neil “Fireball” Roberts:

http://www.ozebiz.com.au/racetech/theory/shocktune1.html

There are some people who will feel that aspects of this are incorrect, but for me, it has worked, and it fits in well with what my gut/intuition tells me is happening at each tire in different phases of the corner.

Now, when Neil talks about bump and rebound, he is talking about their low-speed elements. High-speed shock tuning doesn’t usually come into play for tuning handling – it does change how the car works over bumps though.

On the compression side you can see these shocks have an unusual shape – the compression force actually drops at a certain point. This is known as “regressive” valving and was pioneered in F1, to help keep their chassis from getting upset when the cars hit curbs. This allowed them to continue to have big low-speed compression forces to manage the aerodynamics better, but then have a chassis that became super soft and compliant (relatively speaking) when presented with a big obstacle.

We don’t have curbs in autocross but our sites do occasionally have bumps, and in theory this approach should help keep that big heavy rear axle more compliant over those bumps, while still providing a good measure of traditional low-speed control.

The additional adjustment (“Shaft” on the shock dyno) interacts with the High-Speed-Bump settting, to determine at what shock velocity things “blow off” into regressive mode.

Part of what made me interested in this capability in conjunction with a live rear axle car, is the shock’s contribution to axle torque management. The car depends on its leaf springs to control axle wind-up under acceleration and braking. In ’67 the rear shocks were laid out in a “non-staggered” arrangement, with both lower mounts ahead of the rear axle. These cars were notorious for bad axle tramp, and as a partial remedy, in ’68 the shocks were “staggered”, with one lower mount of the shocks ahead of the axle, with the other behind. So, in a ’67, both rear shocks are in bump under acceleration, and rebound under braking.

When a car is accelerating, the front of the diff wants to rotate upwards, which wants to twist the springs in side view. The much-stiffer-than-stock (approx. 3x) springs I’m starting with will help this somewhat, but the big (1.5″) spacer block hurts, as do the high-grip tires and increased horsepower.

Axle tramp or hop is a violent condition when a wheel/tire begin to bounce, suddenly becoming loaded then unloaded. Not only does it kill acceleration off the starting line or out of a corner, it can also destroy the beefiest of parts. For an example of how it can look, check out the 1:13 mark of this Mustang driver being a hooligan on the streets of San Francisco – granted that was in reverse, but the principles are the same.

Axle tramp can be cured with 75lb. torque arm setups, but I’m hoping that with this range of valving characteristics, it can be sufficiently mitigated with the right shock settings. Sometimes, stiffer valving isn’t the solution.

Sorry not much picture content at this time – have the rear shocks mounted on the car, but the remote reservoir canisters are dangling loose. Darn those canisters!!!

[…] an unknown initial setting (which turned out to be full stiff) to full soft in all 4 adjustments (rear shock description). In general in a powerful RWD car I like the rear shocks set a little softer than you might want […]